Investment Control Act: Swiss Government Proposes Minimal Solution

Abstract

On December 15, 2023, the Swiss Government published a draft Investment Control Act. As compared to the preliminary draft of last year, the draft bill is a minimal solution with a significantly reduced scope of application. According to the draft, acquisitions of Swiss undertakings shall (only) be notifiable if:

- a foreign state investor acquires control;

- a (security-)critical sector is concerned; and

- certain de minimis or turnover thresholds are exceeded.

The draft Investment Control Act is now being tabled in the Swiss Parliament for deliberation. It is expected to come into force in 2025 at the earliest.

A. Overview

On December 15, 2023, the Federal Council (the Swiss Government) adopted the dispatch on the Investment Control Act (Dispatch ICA). As compared to the preliminary draft of May 18, 2022 (PD-ICA; see Homburger Bulletin of May 19, 2022), the draft Investment Control Act (D-ICA) has undergone significant changes based on the results of the public consultation: in the public consultation, many stakeholders had militated against the introduction of an investment control at least or at least argued in favor of limiting its scope. The Federal Council continues to consider that an investment control regime would weaken Switzerland’s positions as a business location. It has hence drawn up a draft law that is «as targeted as possible» – by limiting the scope of application to acquisitions of Swiss undertakings by foreign state investors in critical sectors[1].

At the heart of the debate surrounding the introduction of investment control is the balancing of the economic interest in openness to foreign investment, which is important for Switzerland as a business location, against the security policy interest in protecting public order and security from politically motivated takeovers by foreign investors:

- Economic interests. Foreign direct investment is associated with positive welfare effects, such as an increase in capital stock and the associated use of new technologies and product and process innovations (Dispatch ICA, p. 68).

- Security policy interests. At an international level, the potentially problematic influence of foreign investors, concerns of security of supply and the protection of strategic and critical goods have increasingly come to the fore. According to the regulatory impact assessment conducted, investment control can contribute to the protection of public order and security in some sectors, including armaments and dual-use goods, security-relevant IT services as well as pharmaceuticals and medical devices (Dispatch ICA, p. 66).

Historically, Switzerland has pursued an open policy towards foreign direct investment and has given priority to economic interests, flanked by sector-specific provisions. It is currently unclear whether Parliament will follow the Federal Council’s minimal solution in its deliberations on the draft law, adopt further sector-specific rules[2] or extend the scope of investment control in favor of security policy interests.

B. Main Elements of the Draft Investment Control Act

1. Purpose

The object of protection of the D-ICA is public order and security in Switzerland.

Comment. The D-ICA shall not pursue any further objectives such as preventing distortions of competition through foreign investments or protecting jobs in Switzerland. As compared to the previous draft, the proposed law’s object has been implemented more consistently in that the approval criteria no longer take into account whether the takeover will result in significant distortions of competition. This corresponds to the customary international standard for investment control regimes, which generally pursue security policy objectives – competition objectives are to be realized via competition and/or state aid law, for example.

2. Transactions Subject to Approval (Threshold Criteria)

2.1 Overview

According to the D-ICA, a transaction is subject to approval under the following cumulative conditions:

- A takeover;

- of a domestic (Swiss) undertaking;

- by a foreign state investor;

- in a (security-)critical sector;

- above a certain de minimis or applicability threshold.

2.2 Scope of Application

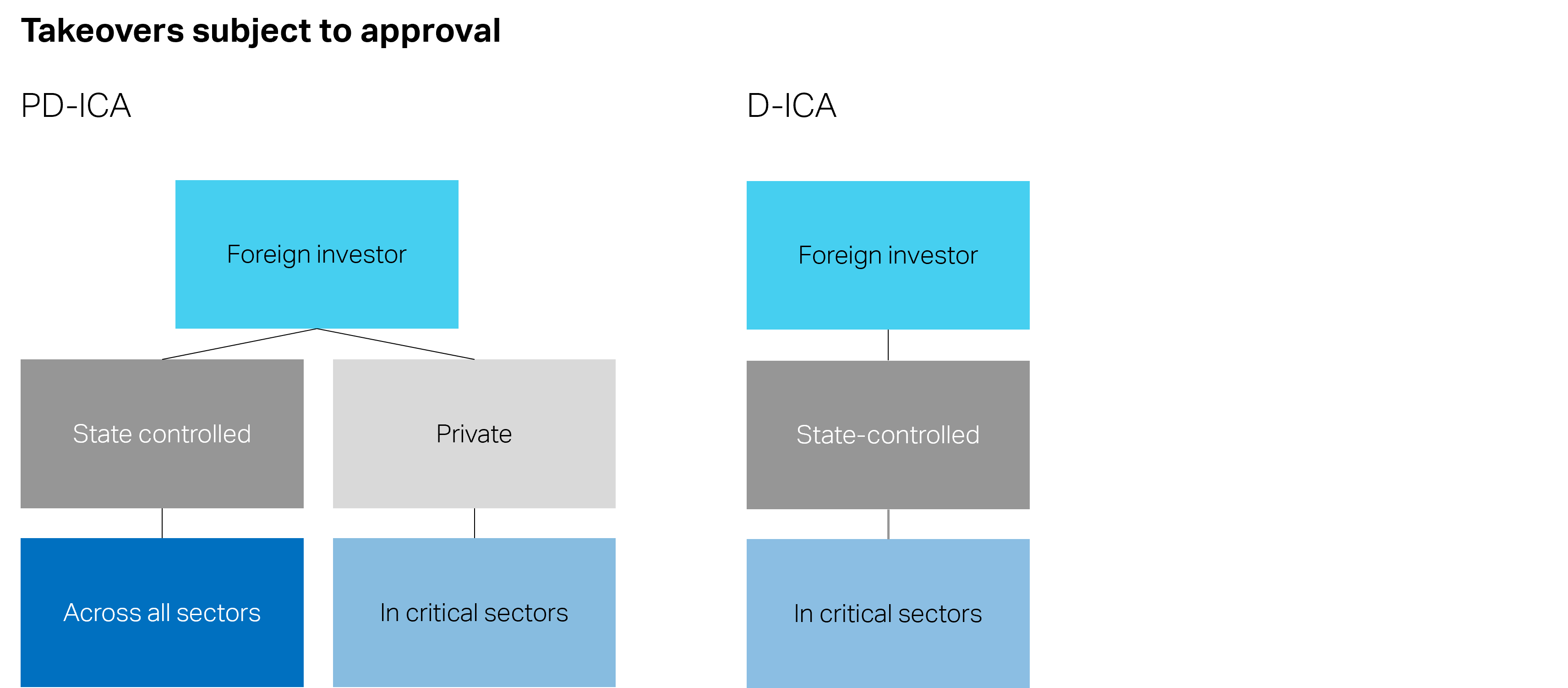

As compared to the preliminary draft, the scope of application is limited as follows (see the below figure):

- No longer will all takeovers by state-controlled foreign investors be subject to investment control, but only those in critical sectors;

- Takeovers by private foreign investors are not subject to approval, even if they concern one of the critical sectors.

Source: Dispatch ICA, p. 11

2.3 The Threshold Criteria in Detail

2.3.1 Takeover

The concept of takeover (Article 2(a) D-ICA) is based on the concept of acquisition of control under merger control law pursuant to Article 4(3) of the Cartel Act (CartA). Control is assumed if the investor has the possibility of exercising decisive influence upon the activities of another undertakings by determining the essential decisions of management and the general business policy (Dispatch ICA, p. 36). Therefore, unlike in Germany or France, for example, there is no approval requirement for the acquisition of a certain minority shareholding without the acquisition of (sole or joint) control.

Comment. Relying on established merger control practice seems appropriate and increases the predictability for the undertakings subject to a possible approval requirement, which have to carry out a self-assessment. The view expressed in the Dispatch ICA (p. 37), according to which the formation of a joint venture with joint control by (at least) two undertakings always constitutes a takeover in the sense of investment control law, even if it is not a full-function joint venture, should therefore be questioned. This difference to merger control law (Article 2[2] of the Merger Regulation) should be avoided, as it opens the door to an autonomous concept of concentration in the area of investment control and would make the application of the law more difficult.

2.3.2 Domestic (Swiss) Undertaking

The definition of an undertaking (Art. 2[b] D-ICA) is based on the functional understanding under competition law (Article 2[1bis] CartA).It is therefore decisive for the qualification as an undertaking whether or not it is a consumer or supplier of goods or services active in commerce.

Any undertaking that is registered in the Swiss commercial register is deemed to be domestic (Article 2[c] D-ICA). This is appropriate in the interests of legal certainty, as the formal criterion of entry in the commercial register is clear and practicable. Based on the results of the public consultation process, the Federal Council has rejected the option put forward for discussion, according to which only undertakings entered in the Swiss commercial register that are not part of a group of undertakings headquartered abroad are captured.

2.3.3 Foreign State Investor

A foreign investor is any person or entity whose head office is located outside Switzerland and who intends to take over a domestic undertaking.

A foreign investor shall be deemed to be state-owned in the following cases (Article 2[d] D-ICA):

- foreign state bodies that act directly as investors;

- undertakings that are directly or indirectly controlled by a foreign state body;

- individuals or corporations acting on behalf of a state.

The practically most important case of control of an undertaking by a foreign state body refers to the concept of control known from merger control already described in connection with Article 2(a) D-ICA. Relevant criteria to assess control are rights of the state body regarding (Dispatch ICA, p. 40):

- appointment and dismissal of members of the management;

- approval of budget, business plan or investments;

- strategic decisions of the foreign investor.

It will make sense to refer to the established merger control practice of the European Commission, which recognizes the following criteria to assess control of state-owned undertakings:[3]

- the autonomy of the state-owned undertaking from the state in determining its strategy, business plan and budget;

- the ability of the state to coordinate business conduct by prescribing or facilitating coordination.

Comment. In light of the regulatory purpose mentioned above, a politically motivated takeover that could potentially impair public order and security is not to be expected as long as no acquisition of control takes place. Unwanted effects in connection with participations by foreign state investors without the acquisition of control – e.g. financing, tax and information advantages, cross-subsidization – need be addressed by alternative regulatory concepts outside of investment control.

2.3.4 Security-critical Sectors

The D-ICA identifies particularly critical sectors for public order and security and distinguishes between sectors (i) with a de minimis threshold and (ii) sectors with a turnover threshold. According to the proposed regulatory concept, only takeovers in these critical sectors by foreign state investors are subject to approval.

From the Federal Council’s point of view, the most sensitive areas with a mere de minimis threshold are to be found in undertakings (Article 3[1] D-ICA),

- that manufacture goods or transfer IP rights that are of crucial importance for the operational capability of the Swiss Armed Forces, other Swiss Federal security institutions and space programs, provided that their export abroad is subject to authorization under the War Material Act (WMA; armaments) or the Goods Control Act (GCA; in particular dual-use goods);

- that operate or control the domestic transmission grid, distribution grids, power plants or high-pressure natural gas pipelines;

- that supply at least 100,000 inhabitants with water;

- that provide central security-related IT services.

In contrast to the preliminary draft, not all takeovers of undertakings that manufacture goods requiring a license under the WMA or the GCA will be subject to investment control. Instead, approval is only required if the goods in question are of crucial importance for the operational capability of the Swiss Armed Forces, federal security institutions or space programs.

The security-critical areas with a turnover threshold are (Article 3[2] D-ICA):

- Hospitals;

- Undertakings in the pharmaceuticals, medical devices, vaccines and personal protective equipment sectors;

- Undertakings that operate or control major domestic hubs (ports, airports, transshipment facilities for combined transportation);

- Undertakings that operate or control railroad infrastructure;

- Undertakings that operate or control food distribution centers;

- Undertakings that operate or control domestic telecommunications networks;

- Undertakings that operate or control financial market infrastructures and systemically important banks.

These critical sectors were hardly controversial during the consultation process and were overtaken to the D-ICA without substantial changes. Critical key technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, cyber security, energy storage, quantum and nuclear technologies as well as nanotechnology and biotechnology are not included in the security-critical sectors.

In addition, the Federal Council is to be granted the authority under Article 3(3) D-ICA to subject further categories of domestic undertakings to the authorization requirement for a limited period of 12 months (with the possibility of extension for an additional 12 months).

Comment. The authorization of the Federal Council is detrimental to legal certainty and can lead to a discriminatory application of the law if it is used to block takeovers by an unwanted foreign investor. In line with the rule of law, all material requirements for the approval requirement should therefore be enshrined in law. In the event of a serious threat to public order and security, the ordinary instruments of emergency law are available – albeit to be used with due restraint. The competence of the Federal Council to exempt certain foreign state investors from the approval requirement if there is «sufficient cooperation» with these states to avert «threats to public order and security» (Article 3[4] D-ICA) is also not very enlightening. In the absence of more precise legal requirements, the Federal Council will have significant discretion, combined with the risk of a not objectively justified unequal treatment of foreign state investors.

2.3.5 Thresholds

De minimis threshold. The approval requirement does not apply to takeovers in the particularly sensitive area described above if the de minimis threshold for the domestic undertaking (at least 50 full-time employees worldwide and turnover of CHF 10 million in the two previous financial years) is not reached (Article 3[1] D-ICA).

Turnover threshold. There is a turnover threshold for other takeovers in critical sectors. The threshold is reached when the global turnover of the domestic undertaking (including its controlled entities) exceeds CHF 100 million.

Comment. The de minimis and turnover thresholds are justified for reasons of procedural efficiency. In individual cases, however, there is a risk that potentially security-relevant takeovers will be exempt from the approval requirement. One example would be the takeover of a domestic start-up in the field of security-related technology and industry base (STIB) by a foreign state investor after it has developed a disruptive innovation in the defense sector.

3. Approval Criteria (Intervention Criteria)

A takeover subject to notification is approved if, in the context of an ex ante assessment, «there is no reason to assume that […] public order or security is endangered or threatened» (Article 4[1] D-ICA). According to the dispatch, a conceptual risk assessment must be carried out based on the product of the probability of occurrence and the potential damage (Dispatch ICA, p. 46).

The approval criteria are used to assess, in relation to the probability of occurrence, whether the foreign state investor enjoys a good reputation and offers a guarantee of irreproachable business conduct (in particular, no involvement in a criminal organization; no espionage, etc.; Article 4[2][a-d] D-ICA). One of the relevant criteria for the potential damage is the lack of substitutability of the services, products or infrastructures of the domestic undertaking (Article 4[2][e] D-ICA; Dispatch ICA, p. 48).

The preliminary draft still provided for the foreign investor’s willingness to cooperate to be taken into account in the approval decision (Article 5[3] D-ICA). This provision was rightly deleted without replacement, as the willingness to cooperate is not a suitable criterion for assessing the danger or threat to public order or security. As already mentioned, the creation of distortions of competition is also no longer included in the intervention criteria under Article 4 D-ICA.

Overall, the intervention criteria leave the authorities substantial discretion in line with the security policy goals of the investment control. Security policy is a prerogative of the executive, which is why the latter must substantiate the undefined legal concepts of public order and security on a case-by-case basis based on the actual risk situation.

4. Procedure

4.1 Preliminary Clarification

In contrast to the preliminary draft, a so-called «preliminary clarification of the approval requirement» was included in the draft law in response to suggestions made during the public consultation process. This instrument is not binding and is intended to enable the undertakings involved to clarify whether they are likely to be subject to an approval requirement (Dispatch ICA, p. 49).

Comment. In practice, this preliminary clarification is likely to remain largely ineffective. To obtain legal certainty regarding the notification obligation, the undertakings concerned must submit a notificationas part of the binding approval procedure. Instead of a preliminary clarification, they may be inclined to submit a notification in the binding approval procedure to establish the absence of an approval requirement, combined with a request that the takeover shall be approved in the alternative.

4.2 Approval Procedure

The approval procedure provided for in the D-ICA is leaned on the merger control procedure. The foreign investor must notify the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) of the takeover requiring approval prior to its completion (Article 6[1] D-ICA). The effectiveness of the takeover under civil law is postponed until approval is granted (Article 8[4] D-ICA). There is a standstill obligation, which can be enforced with administrative measures (Article 17 D-ICA) and sanctioned with administrative penalties of up to 10% of the worldwide annual turnover of the undertaking resulting from the takeover (see Article 18 D-ICA). This sanction is considerably more drastic than the corresponding regulation in merger control, where a violation of the standstill obligation can be sanctioned with a maximum of CHF 1 million.

SECO is entrusted with the implementation and coordination of investment control. It makes its decisions in consultation with the so-called co-interested administrative units, which it designates on a case-by-case basis (Article 10 D-ICA). Only units of the central Federal administration are eligible, whereby the State Secretariat of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) and the newly created State Secretariat for Security Policy (SEPOS) are always considered to be co-interested parties.

A two-stage review procedure is provided for (Article 6 et seq. D-ICA):

- Phase I. Within one month of receipt of the complete notification, SECO decides, in agreement with the co-interested administrative units and after consulting the FIS, whether the takeover can be approved directly or whether a review procedure must be initiated (Article 7[1] FNIA). SECO and the co-interested administrative units each have a right of veto: if no agreement can be reached between them, a review procedure (Phase II) must be initiated (Article 7[2] D-ICA).

- Phase II. As part of an in-depth review, SECO decides within three months of the initiation of the review procedure whether the takeover will be approved; the decision is made in consultation with the other interested administrative units and after hearing the Federal Intelligence Service (FIS) (Article 8[1] D-ICA). If SECO or a co-interested administrative unit opposes the approval or if the decision has significant political implications, the approval authority is transferred to the Federal Council (Article 8[2] D-ICA). Only the Federal Council can decide to block a takeover (Article 8[2][a] D-ICA).

Comment. The two-stage procedure, which has proven itself in merger control law, seems appropriate. Similar to merger control, Phase I only begins with the receipt of the complete notification; SECO confirms the completeness of the notification (Dispatch ICA, p. 51). This indicates that a pre-notification procedure modeled on merger control practice should be possible.

4.3 Legal protection

The preliminary draft provided for a judicial review to be limited to compliance with procedural guarantees or the existence of an abuse of discretion in cases «of considerable political significance» (Dispatch ICA, p. 19). This was criticized in the public consultation process, particularly with regard to the separation of powers. The D-ICA takes this criticism into account by refraining from restricting judicial review in cases of considerable political significance (Dispatch ICA, p. 19). In principle, only the foreign investor and the domestic undertaking have the right to appeal (Article 18[2] D-ICA).

C. Practical Impact and Outlook

With the D-ICA, the Federal Council is further restricting the scope of the Investment Control Act. If the investment control is implemented in accordance with the Federal Council’s draft bill, private foreign investors would not be affected. Based on the current draft law, it is estimated that only a low single-digit number of takeovers will require approval each year. Switzerland would thus remain open to foreign direct investment, while the differentiated framework of sector-specific regulations would remain applicable for private foreign investors.

In practical terms, the draft law remains particularly important for foreign state investors, who will have to be prepared that an approval requirement may apply in future if they make investments in one of the critical sectors. In the case of potentially problematic takeovers, it is advisable to make contractual provisions for a possible longer review period or non-approval.

The draft bill will now go into parliamentary deliberation and may still undergo significant changes. The Investment Control Act is not expected to come into force before 2025.

[1] Federal Council opinion of June 2, 2023, on the report of the Environment, Spatial Planning and Energy Committee of the National Council of March 28, 2023, Parliamentary Initiative (16.498) Subordination of the strategic infrastructures of the energy industry to the Lex Koller, BBl 2023 1452, p. 9.

[2] Additional sector-specific regulations are currently being discussed in connection with the so-called postulate «Pult», according to which the Telecommunications Act should be supplemented with a set of instruments based on the model of the 5G toolbox at EU level, which would allow measures to be taken against suppliers under the influence of a foreign state if geopolitical risks were to materialize in order to protect the telecommunications infrastructure. See postulate «Pult» (20.3984) of September 14, 2020 «Digital infrastructure. Minimizing geopolitical risks».

[3] COMP M.7850, EDF/CGN/NNB Group of Companies, paras. 29-50; COMP M.7643, CNRC/Pirelli, paras. 8-21; COMP M.7962, ChemChina/Syngenta, paras. 81-88.

If you have any queries related to this Bulletin, please refer to your contact at Homburger or to:

Legal Note

This Bulletin expresses general views of the authors as of the date of this Bulletin, without considering any particular fact pattern or circumstances. It does not constitute legal advice. Any liability for the accuracy, correctness, completeness or fairness of the contents of this Bulletin is explicitly excluded.